The dim silhouette of Maine’s Long Island began to emerge against the rugged backdrop of Mount Desert Island at around 6:00 a.m. on Tuesday, June 12, and when the American Promise glided into the lapping waters of Frenchboro Harbor, the raw beauty of the tiny island was already unmistakable. The American Promise, the 60-foot sailboat that serves as the mobile headquarters of the Rozalia Project, took up mooring about a tenth of a mile off the coast. Long Island is located halfway up the coast of Maine, a few miles south of Bar Harbor. The island, home to the small town of Frenchboro, was one of the first stops on the Rozalia Project’s Summer 2012 Trash Tour.

The eight members of the Rozalia Project’s trash collection crew met with Terry Towne, our contact with the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, at 10:30 a.m. Terry would serve as an indispensable hiking guide, naturalist, expert in Frenchboro life, and storyteller in the days of trash collection to come. We learned from Terry that Frenchboro is a tiny fishing village that consists of 32 year round residents. The town encircles the all-important harbor, consists primarily of a few clusters of waterside cottages, and boasts a beautiful colonial-style church, a library, a small school which accommodates Frenchboro’s 11 children in the grades K-8, a small municipal building, and two small waterside eateries. As we puttered into Lunt’s harbor on two small dinghies, the multitude of Frenchboro’s fishing piers came into view, the stacks of lobster traps and colorful rope-coils atop them revealing Frenchboro’s life-sustaining industry. The nucleus of the Frenchboro community, the harbor seemed alive with the brine-crusted vessels of fishermen. Mighty stacks of lobster traps sat like wire skeletons atop barnacle-covered sepulchers in the morning fog.

We followed Terry through the tiny village and on a stunning two-mile hike across the island. Our hike took us through the Southern fringes of the boreal forest to the Southeastern edge of Long Island. We emerged from the scrubby pines of the forest to an overwhelmingly beautiful vista. From our vantage point, we looked out over a beautiful, grassy isthmus of no more than 50 yards in width, fringed on either side by two rocky beaches. Ahead of us lay a knobby, spruce-covered peninsula ringed by coarse reefs and weathered rock columns. Around us, the seas were festooned with lobster buoys of every imaginable hue. This beautiful place was Rich’s Head, our cleanup site.

We stopped to eat a quick lunch in the middle of this postcard, and then we set to work for our first day of cleaning. The beaches were even rockier than they had first appeared, and the smooth, larges stones obscured from view an incredible amount of debris. The beaches were littered with thousands of pieces of trash that had escaped notice in our initial survey of the peninsula. We discovered food wrappers, derelict fishing traps, buoys, plastic bottles, bait-bags, bits of rope, and other fishing materials. The sheer volume was quite shocking; it struck me immediately that our three days in Frenchboro would be scarcely enough time to clean up all of the debris before us. We cleaned at an energetic pace; on the first day of pickup, we managed to pick up 3,112 pieces of trash in just three hours.

We returned to Rich’s Head the following day and continued our work despite inclement weather (it rained for most of the day). We were astonished at the amount of debris concentrated in the large drift pile that sat towards the middle of the isthmus leading to Rich’s Head. The thousands of buoys that we had circumvented en route to our mooring in Lunt’s Harbor had formed a similarly vivid mosaic of color in the large drift piles of the isthmus. Not only was the trash scattered along the whole length of the beach, but also, amazingly, it was vertically layered in heap after heap of driftwood. After a day of scouring the drift piles, we managed to pick up a staggering 4,798 pieces of trash on our second day of collection.

Rather than cleaning the twin beaches of the isthmus as we had done for the previous two days, we trekked further along the peninsula on our third and final cleanup day. We got to enjoy some of Maine’s best most beautiful hiking trails as we zigzagged through mossy knolls on the way to our new location. After about a ten-minute walk from our initial cleanup location, our team emerged onto a rocky plain littered with buoys and plastic bottles. We had just begun to pull on our work gloves and stuff our bags full of garbage when our guide Terry rounded the bend behind us, laughing at our efforts. Not finding the heaps of buoys and bottles particularly amusing, we shot Terry a volley of quizzical looks. “Oh this isn’t the spot,” he told us. “Once you see how much trash is out further on the point, you’ll have your hands full, believe me.”

Terry wasn’t kidding. Lying on the side of the hiking trail that looped around Rich’s Head were heaps of trash so large it looked as though people had already piled them for us. When we walked out further onto the rocks, however, the debris only seemed to multiply. At the conclusion of this third day, we had amassed a pile of more than 4,256 huge pieces of debris, ranging from a propane tank to a Styrofoam-filled piece of plastic dock material.

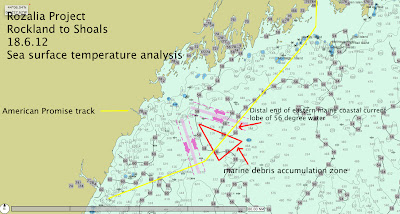

We found it staggering that such a high volume of trash could accumulate in a location as seemingly remote as Long Island. Our visit to Frenchboro was a dramatic example of the interconnectedness of all ocean-goers. A unique feature of the ocean, one as beautiful as it is dangerous, is that no part of the ocean can truly be remote. The mounds of trash on Rich’s Head were a vivid reminder of the ocean’s tremendous capacity to act as a conveyor belt that can swallow up and parcel out its cargo to the remote corners of the world. We found pieces of trash imprinted with a half-dozen different languages, and pieces of fishing gear that had undoubtedly come from all up and down the coast. In fact, while working on the beaches of Rich’s Head, Terry had told us that he and his crew had done a thorough cleanup of the very same site just three months before our arrival, which was a frightening reminder of how quickly trash can pile up.

It was incredibly satisfying to see the beaches transformed from a veritable garbage heap to their natural beauty over the course of our three-day cleanup project on Long Island. In total, we picked up 12,166 pieces of trash during our three-day cleanup of the Rich’s Head beaches. However, despite the great work we were able to accomplish during our time on Long Island, our conversation with Terry about his unceasing efforts to keep Long Island debris-free left us with an important and sobering reminder of the importance of continuing to encourage responsible recycling practices. It is important to remember that the Rozalia Project is only part of a broader coalition to clean the world’s ocean. Although it may seem hard to believe to a visitor of remote Frenchboro, the recycling decisions made by consumers of recyclable goods in Miami, Shanghai, Tokyo, and São Paolo all affect the health of Long Island’s beaches. To preserve the beauty of Rich’s Head, it is important for not only New England fishermen, but all those who enjoy the coasts of the world to realize their ocean-sized affiliation with one another.

This blog post was written by Rozalia Project's Embedded Journalist and little-bit-of-everything Intern, Conot Grant. Conor will be with us through the middle of July. Keep an eye on this page for more of Conor's experiences and observations as he travels with American Promise and Rozalia Project writing about our work (and getting his hands salty and sandy).